Aesthetics of Resistance: The Ways of Spatializing Women’s Ecological Struggle in Turkey

The environmental movement of Turkey has three decades of history. A culture of resistance was transferred from the first women’s ecological resistance that attracted attention in the Bergama peasant movement to today’s struggling women.[1] One of the areas of resistance discussed in this article is the Mount Ida (Kazdağları) Resistance, which is one of the most reported ecological struggles in the press in recent years in Turkey. [2] Global companies came to this significant area, within the borders of Turkey’s Marmara and Aegean regions, to search for gold with cyanide and destroy some regions with the state’s approval. Resistance temporarily stopped the destruction and cutting of trees in the area. However, mining companies are always trying to re-occupy the area. The other resistance examined in the article is the Akbelen Forest Movement. The resistance against a lignite mine that is desired to be established in Muğla city is ongoing. [3] These are merely two examples of ecocides that women in Turkey have come to the fore to challenge.

Applying the lens of sustainability, unfairness, and inequality in politics has moved discussions in ecological movement studies forward in recent years. It is revealed that there is a gender sensitive dynamic within the movement seeking environmental and social justice, while challenging the destruction of natural assets and ecological commons. Studies apply an ecofeminist perspective to existing socio-economic and ecological crises. I suggest basing research in feminist political ecology,[4] which can conceptualize women’s activism in the local, and on urban political ecology,[5] which can problematize the urban-rural, nature-society, or urban-nature segregation. The resistance that is seen at first glance as a nature conservation effort by villagers in the rural areas, actually is a ruralized-urbanized meeting. It is driven by an impulse to destruction created by modern urbanization.

In the first stage of this study, I conducted in-depth interviews with villagers and outsiders who are independent activists or belong to different environmental associations. I took photos and video recordings related to any kind of physical formation in the resistance areas. Afterwards, I organised mental mapping practices[6] and exposure walks with participants in the villages, resistance areas and any relevant natural areas. I focused on gender differences. I also collected archival files and documents of the villages.

There are not only peasant women and local people in these struggles. Environmental activist women who came from „outside“ and grew up in a relatively urban culture make great efforts to make rural women visible. This phenomenon can be understood through spaces in which actors contribute to forms of experience that create new sensations and reveal unique political characteristics. The „outsider“ and the „insider“ encounter each other in the living spaces of the rural areas that they are trying to protect. These encounters, interactions, and frictions create completely different relationships and phenomena. In fact, this ecological struggle makes two-sided transmissions in the space where „ruralized“ and „urbanized“ women meet, become partners, differentiate, separate or transform. The reflexes produced by the people from the village and those coming from the city can produce a new kind of radicalism that emerges thanks to this mutual interaction.[7]

To comprehend this interaction, it is necessary to understand the existing relations in the village. While the village is a very restricted and self-enclosed area, it is also a living space that needs to be protected. For this reason, these encounters turn into both a very risky and an essential phenomenon. For example, while village women want to join the resistance in the village where patriarchy is felt very much, they can be prevented by the men in their families. For the sustainability of resistance, peasant women need to be persuaded and informed about the damages and threats the mining companies pose to their lands, water resources, animal stocks, and so on. On the other hand, the outsider must respect the living space and lifestyle of the villagers. At the same time, in these long-term struggles, the outsider must meet basic survival needs. Ultimately, all groups of women need to cooperate with each other to be more visible and resilient. Because those coming from the outside can also be exposed to the male dominance both existing in the village and in their own ecological associations. In short, the environmental struggle can actually turn into a struggle for life by women.

Learning the forest’s knowledge from the villagers, and experiencing resistance culture with urbanized people, respectively, reveal new perspectives. This interaction can bridge the nature-urban segregation. Besides, women can emphasize the ambiguity specific to the protection of nature, natural assets and ecological commons. There is an “aesthetic experience” that attracts attention and stands out from today’s male-dominated and modern urban world; the aesthetics of dichotomies, the aesthetics of resistance.

The notion of resistance has an aesthetics dimension. “Aesthetics” used here is not to question women’s local resistance through the value of beauty and ugliness. Jacques Ranciere describes aesthetics as a concept that helps us look at the potential radicalism in the transitions between art and politics. According to Ranciere, aesthetics describes the forms of experience that create new sensations and reveal new political features.[8] I examine the aforementioned environmental struggles through the lens of an “aesthetics experience” which is made visible in an ethical and political framework. In short, my work stands at the intersection of architecture and sociology, the creative thought of the “aesthetics political act”.[9] It serves to highlight the ambiguity of the urban-rural segregation emerging from the spatial compositions produced by the women in the environmental movements.

The spatialities of women’s ecological struggles

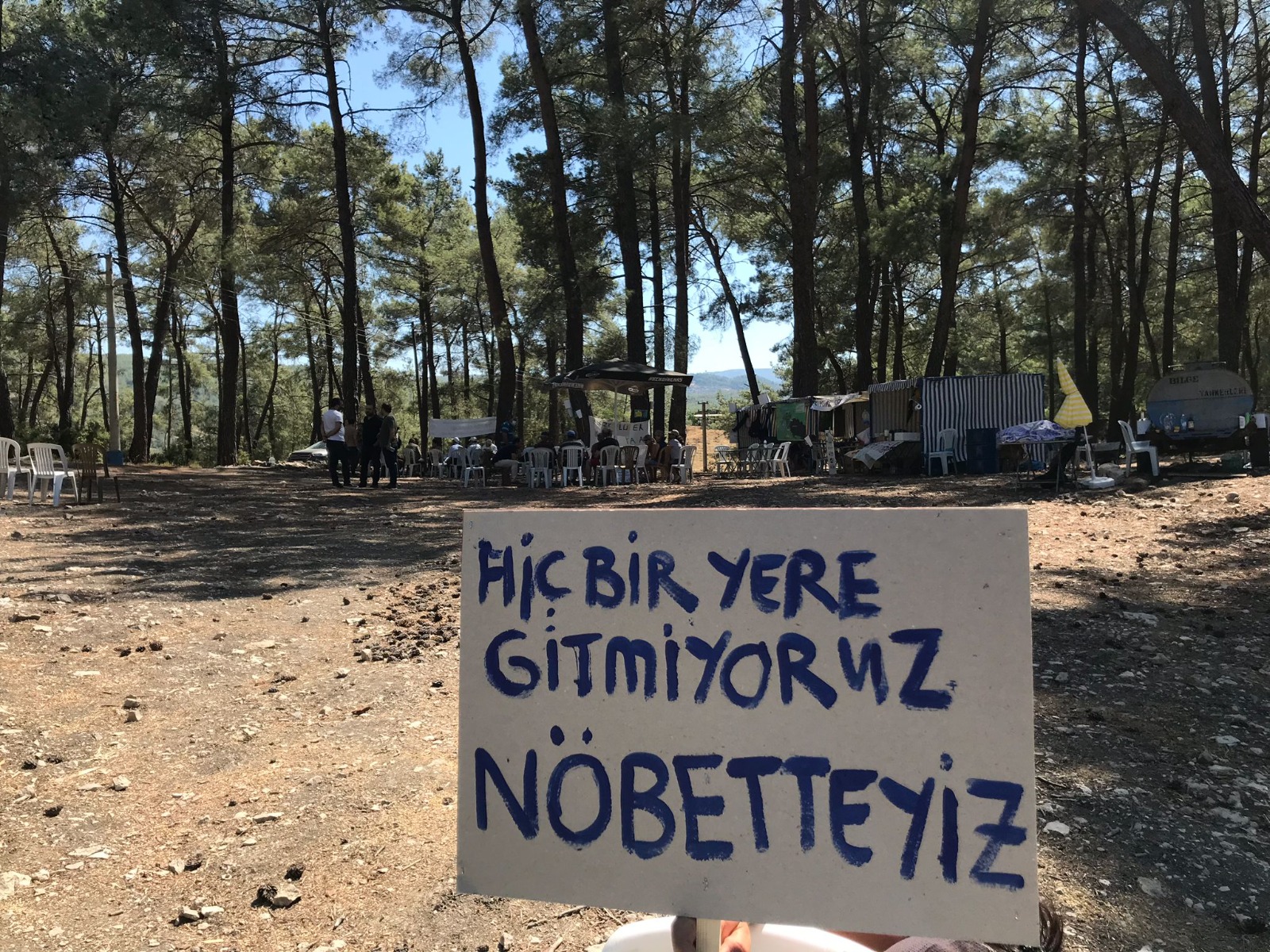

Women’s ecological struggle in these spaces is shaped by spatial determinations in several ways. First, women accept the whole forest and the whole mountain as their „living space,“ which is reflected in their resistance style. By seeing the forest as a living space or purpose for living, women want to stand there and resist more permanently. As a result, women and their actions have come to the fore in ecological movements.

Villagers help the activists get to know the forest and the mountain, introduce their habitats, help to explore places where resistance will occur, and to meet their survival needs. In addition, the words they use when describing the forest and the paths they walk are different from those of men. However, the collaborations and relations established may differ according to the geographical and cultural characteristics of the villages.

For example, while resisting, women activists make a point of establishing a more permanent place. Instead of temporary resistance tents, they are restoring and transforming an existing place in the forest, which they call the „occupied house“. Although the village women can visit the resistance tent in the daytime, it is almost impossible for them to show collective solidarity with the activists in these areas at night due to the patriarchal order. Activists try to break this pattern by persuading village women’s families.

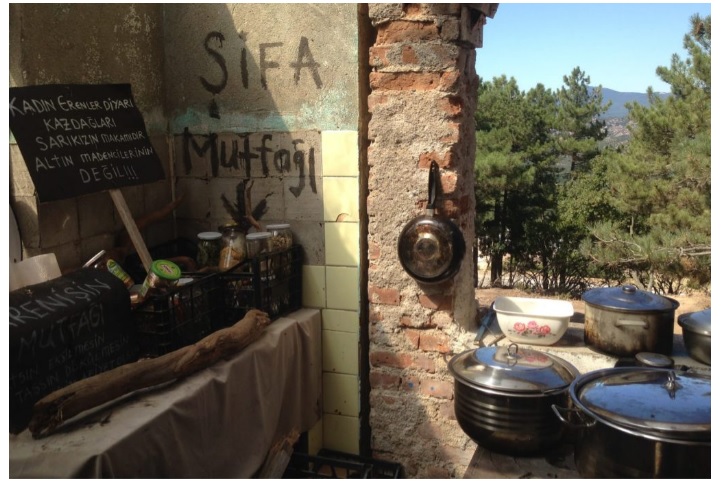

Activists constructed a “resistance kitchen” in the forest which is seen as their home. Village women also cook in this kitchen to give out food to the resisters.

Moreover, the „village coffeehouse“, which is only used by men, has been shared with women in the resistance process. Thus, the perception of the space and social norms changed in that period. [10] The coffeehouse can turn into an education centre where village women are made aware by the activists of all the threats that arise from the false promises of the mining companies.

At certain times, law enforcement officers change the location of resisters where they set up their tents and containers. They try to hamper resisters setting up locations in the middle of the forest. However, activists aim to defend their places inside the forest where they feel they belong, rather than being relegated exclusively to the forest’s boundaries.

Within these resistant spatial forms, some ruralized and urbanized reflexes come together and co-exist. For instance, the occupation of a building, that is, the reconstruction and repair of the occupied house, is an urbanized reflex. But those who show the existing building in the forest and give outsiders the right to use it are the villagers. Thanks to the solidarity between both, the building is put into use. While the urbanized people use resistance tents, the villagers sleep in the tractor box. The villagers here are used to sleeping like this when they go to the plateau. While environmental activists use dry toilets, villagers don’t need them.

Because of the intersections experienced, both the villager and the activist woman are changed. The village women occupy masculine spaces and experience changes to the concept of time-space, while urbanized women hear/perceive/feel nature and their alienation to some modern urban/urbanized notions. Transitions in a small area of resistance experienced by these women can affect the nature-urban segregation of the whole society. This becomes clear when we look at the effect this struggle arouses in the media. It creates important symbols, provides examples of sustainability, and contains a creative alternative thinking power that can question contemporary urban people’s way of thinking. However, external interventions could damage the „affective composition“[11] of the resistance. In other words, while the symbols in the ecological struggle, from an ecofeminist perspective, are sustainable and lively, it can easily become a target for the reification, commodification, and fetishization of activist creativity. This study strives to make visible all of these phenomena through a perspective of spatial struggle. While social sciences frequently have conceptual discussions in these areas, the discipline of architecture remains relatively removed. However, as physical space editors, architects can offer suggestions to reveal the potential that producing alternative lifestyles of the resistance developed against the occupation of living spaces.

Autor*inneninfo

Özden Senem Erol is an architect and senior at the sociology department. She completed her PhD degree in architecture at Kocaeli University, and she is close to graduating from sociology at Middle East Technical University (METU).

Referenzen

[1] Çoban, A. (2004). Community-based Ecological Resistance: The Bergama Movement in Turkey. Environmental Politics, 13(2), 438-460. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000209658

[2] Özdemir, E. (2022). Gold Mining Activities in Turkey’s Mount IDA (The Kaz Dağları) Has Sparked Environmental Protests. DoYouKnowTurkey. Retrieved 15 September 2022, from https://www.doyouknowturkey.com/gold-mining-activities-in-turkeys-mount-ida-the-kaz-daglari-has-sparked-environmental-protests/.

[3] Akbelen struggle gives hope in these difficult days – Europe Beyond Coal. Europe Beyond Coal. (2022). Retrieved 15 September 2022, from https://beyond-coal.eu/2021/08/16/akbelen-struggle-gives-hope-in-these-difficult-days/.

[4] For feminist political ecology studies, see;

– Rocheleau, D., Thomas-Slayter, B., Wangari, E. (Ed.) (1996). Feminist Political Ecology. Routledge, London.

– Elmhirst, R. (2011). Introducing new feminist political ecologies. Geoforum, 42(2), 129-132.

– Harcourt, W., Nelson, I. (2015). Practising feminist political ecologies: Moving beyond the green economy. Zed Books.

– Schroeder, R.A. (1996). ‘‘Gone to their second husbands’’: Marital metaphors and conjugal contracts in the Gambia’s female garden sector. Canadian Journal of African Studies, 30 (1), 69–87.

[5] For urban political ecology studies, see;

– Coates, R. (2019). Citizenship-in-nature? Exploring hazardous urbanization in Nova Friburgo, Brazil. Geoforum, 99, 63-73.

– Soens, T., Schott, D., Toyka-Seid, M., De Munck, B. (Ed.). (2019). Urbanizing nature: Actors and agency (dis) connecting cities and nature since 1500. Routledge.

– Rice, S., Tyner, J. (2017). The rice cities of the Khmer Rouge: an urban political ecology of rural mass violence. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 42(4), 559-571.

[6] For mental mapping practices, see;

– Jung, H. (2012). Let their voices be seen: Exploring mental mapping as a feminist visual Methodology for the study of migrant women. International Journal Of Urban And Regional Research, 38(3), 985-1002.

– Self, J., & Hudson, K. (2015). Dangerous waters and brave space: A critical feminist inquiry of campus LGBTQ centers. Journal Of Gay &Amp; Lesbian Social Services, 27(2), 216-245.

– Gieseking, J. (2013). Where we go from here: the mental sketch mapping method and its analytic components. Qualitative Inquiry, 19(9), 712-724.

[7] To indicate the findings next, interviews are done with environmental activists and village women, and their photographs and video archives are examined. The Ecology Union Women’s Assembly Archive was used for visual sources. The web address of the Ecology Union; https://ekolojibirligi.org/

[8] Rancière, J. (2014). Aesthetics and its discontents. Polity.

[9] Fırat, B.Ö.& Bakçay, E. (2012). Çağdaş sanattan radikal siyasete, estetik- politik eylem. Toplum ve Bilim, 125, 41-62.

[10] Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (2009). The production of space. Blackwell.

[11] Stevphen Shukaitis. Joaap.org. (2022). Affective Composition and Aesthetics: On Dissolving the Audience and Facilitating the Mob Retrieved 14 September 2022, from http://www.joaap.org/5/articles/shukaitis/shukaitis.htm.